It was pleasant to read Anthony Douglas, Chief Executive of CAFCASS, acknowledging that parental alienation was a form of child abuse in this week’s Telegraph. Pleasant… although being honest the main emotion was irritation, as I read an article which did little and said less. Catch up! Alienation is recognised… this isn’t news. If you want a news piece, ask what’s being done about it?

Parental alienation is rarely a disease which strikes without warning. It’s an administered poison, which eats away at the child’s view of the world. As with any poisoning, earlier diagnosis, intervention and prevention presents the best hope of cure. Failing this, the child gets more ill and future interventions become less likely to succeed. What we often see is the judicial ‘doctor’, who has had the child as his patient for months or years blame the parent for the poisoning while abrogating himself of relationship deaths by ignoring his failure to diagnose and treat. For a classic example, read this where the President of the Family Court does this himself.

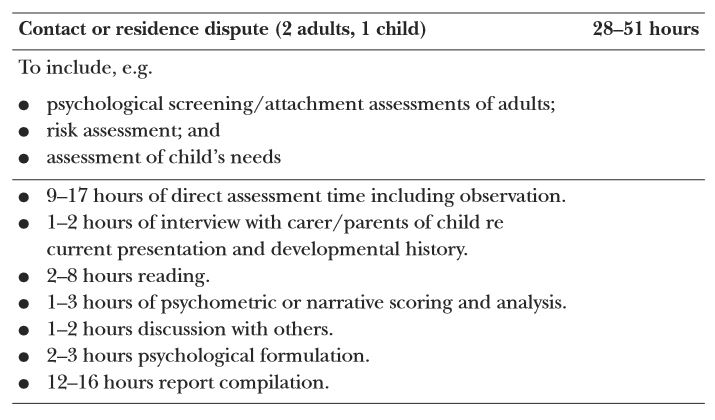

Remember the poisoning scene in the film Sixth Sense… Anthony Douglas recognises that parents are putting bleach into their children’s drinks. Bravo. This rather begs the question of what he and the President of the Family Court are doing to improve outcomes for the affected children, having responsibility for their respective organisations and child welfare. We’re well past the days when the senior courts didn’t accept parental alienation as a factor in intractable contact disputes. There’s case law confirming it can cause significant harm to a child. Training courses within the British Psychological Society (BPS) and judgments recognising the court’s failures. Click the links… read them.

It should come as no surprise whatsoever that Anthony Douglas and Sir James Munby (President of the Family Court) know very well what the problems are. Perhaps the journalist should be asking them what steps they’re taking to improve case management and judicial training to help prevent such harm being caused to children? In fairness to Anthony Douglas, I’ve seen far more improvement in CAFCASS reports in recent years than I have in judicial case management in cases involving alienation. Those improvements though, aren’t universal.

In September 2015 I was asked to write a report by a charity setting out the problems in intractable contact dispute and parental alienation cases. I know Sir James Munby has it, charity representatives met him to discuss the contents. I understand there wasn’t much disagreement about the issues when the report was discussed. You can read the report yourself… here. The Telegraph’s reported idea to have a panel of experts advise the courts and propose more effective interventions isn’t a new thing. In my report, I made the same suggestion, proposing Dr Kirk Weir, Dr Mark Berelowitz and Dr Sue Whitcombe (Dr Whitcombe is currently running the BPS training courses on understanding, intervention and treatment of parental alienation).

In February 2016, a number of the problems my report listed were the subject of judicial acknowledgment in F (Children) [2015] EWCA Civ 1315. Be assured, the problems are known beyond Munby. How many years does it take to turn recognition of a problem to improvement in case management? Case law is all well and good, but unless the lower courts are aware of it, and the guidance it contains, what benefit? How many litigants-in-person know how to present it, if they’re even aware it exists themselves.

Sorry to say that the Telegraph’s article didn’t fill me with hope. It underlined to me that the problems are well know, but there’s a lack of capability, resource or motivation to address them. Perhaps the very structure of the Family Court and Family Justice system prevents professional management of such cases due to poor communication and training? Does individual judicial discretion prevent more professional process being accepted? Does convention trump welfare or is there another reason the same old tired mistakes are made again and again? These are questions I’d like to see posed in the Telegraph… and some answers too.