Data from a Freedom of Information Act request for non-molestation order applications (in 2014) shows that of the 21,162 applications (included in the statistical returns) a little over 60% were made ‘without notice’ (12,769 applications).

Without Notice applications to the court involving claims of domestic violence often result in injunctive orders being made without the accused having had the opportunity to present their own evidence in defense at the time the order is made (the orders being made ‘ex-parte’ which means without the other party being present). Typically, those applications are for non-molestation orders and occupation orders.

These orders have serious implications and can impact upon the respondent’s family life, restrict their freedom of movement and carry a power of arrest if broken.

When such injunctive orders are granted, the applicant is then entitled to legal aid and professional representation. The accused is not. This gives the accuser advantage in future proceedings/hearings if the accused then seeks to challenge the making of the order or there are contested proceedings over arrangements for children.

As well as injunctive orders being made ‘ex-parte’, on occasion hearings are listed on short notice giving the accused little or no chance to prepare. Where orders are made ex-parte, the court is unlikely to have heard any evidence which challenges the allegations. In cases where there is genuine risk of violence to the applicant, there is good reason for the accused not being ‘tipped off’ in advance of the court making precautionary orders. Such caution however has its risks in that, when allegations are false, this can result in the court being a party to coercive control and the accuser having unfair advantage in future proceedings.

Such injustices do arise. In R v R (Family Court: Procedural Fairness) [2014] EWFC 48, Jackson J lists a catalogue of errors by the lower court, and gave comment (at paragraph 1(5)):

“The court should be on guard against the potential for unfairness arising from the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, whereby the applicant is entitled to legal representation as a result of unproven allegations, while the respondent is not. In this case, the fact that one party had no legal advice at any stage was critical to the outcome.”

In that case, the court’s guard was clearly down. That case, sadly, was not exceptional.

There are procedural checks and balances which should mitigate risk. The accused should have a further hearing listed where there is the opportunity to defend themselves. They should be notified of, and have sight of all evidence which was put before the judge when the order was made. They should have the opportunity to file their own evidence. Sadly, such procedures are not always followed. This compounds the injustice caused by one party being represented while the accused is often not.

In B v A [2012] EWHC 3127 (Fam), Charles J states:

“11. Both Theis J and I (in B Borough Council v S) point out in restrained terms that the principles and procedures in respect of without notice applications that are clearly established by authority are regularly not followed in the Family Division.

12. This case provides an example of this. To my mind, this regular and flagrant failure by many practitioners and judges is contrary to the public interest. I, and some of the other judges of the Division, try to bring about necessary and much needed changes when dealing with without notice applications (particularly in the Applications Court). But sadly, this case is a clear demonstration that we have not succeeded and that a number of our colleagues do not take the same approach. So the serious failings are endemic amongst many family practitioners and judges who have been family practitioners.”

The frustration held by some campaigning groups is acknowledged and shared among senior judiciary.

Difficulty for the unrepresented accused comes from a lack of knowledge as to whether the correct procedure has been followed by the court (and/or applicant and their legal representatives). This inevitably interferes with their defending against the order due to their ignorance of procedural irregularity. While instances of procedural unfairness/irregularity do result in successful appeal, a litigant-in-person is often oblivious to the grounds which may exist in their case. Not so much ‘ignorance is no defense’ but ‘ignorance prevents defense’.

Many of these cases are heard in the lower courts where knowledge of correct process can be lacking. Additionally, we see growing instances of complex cases being handed down to magistrates who lack the experience and training of more senior judges. Such occurrences are likely to become more common-place as a result of court closures, austerity and cuts. Unless there is radical change, or legal aid awarded to the accused as well as the accuser (highly unlikely in the current political climate), it is for the litigant-in-person, whether a plumber, cab driver, hairdresser or unemployed to get to grips with complex areas of law when unable to afford legal assistance. In such circumstances, it’s impossible to see how justice in England and Wales is compliant with the human rights act and a right to a fair hearing.

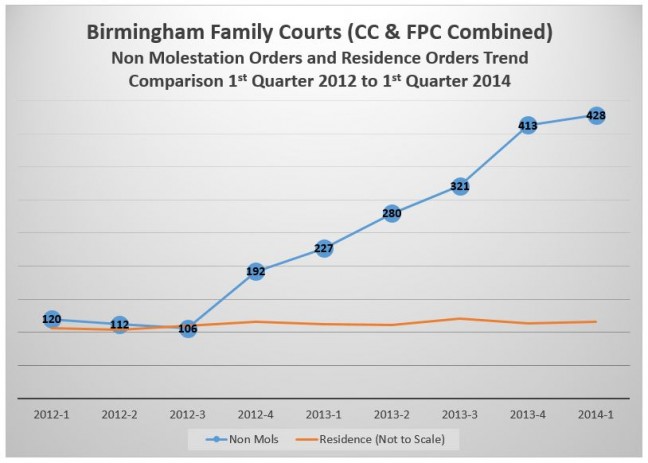

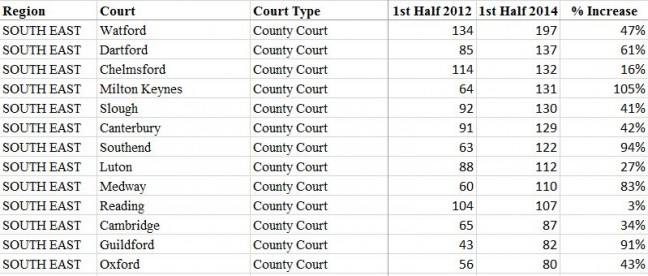

There has been an ‘explosion’ in the number of non-molestation orders being made by the court since legal aid was limited to cases involving domestic violence. The Daily Mail picked up on the subject of a series of articles we ran last year… see ‘Daily Mail: Huge Rise in DV Claims after Legal Aid cuts‘.

To help in these cases, we have a new section in our web site, under our Case Law Menu, entitled Without Notice And Non-Molestation Order Case Law. The purpose is to inform both sides involved in these proceedings as to the correct procedure which should be followed by both the court and applicant in respect of without notice applications for injunctive orders. We will be expanding upon this section in the coming weeks, and also providing a dedicated guide and support tools. In the meantime, we have also made reference in that section to rules related to applications for these types of order (made under Part IV of the Family Law Act 1996).

You may also wish to refer to our existing guides on Domestic Violence, Non Molestation Orders, Occupation Orders, Undertakings, False Allegations and our Occupation Order Case Law Menu.

We also recommend you pay particular attention to paragraphs 13 to 16 of KY v DD [2011] EWHC 1277 which is included in our new section.