Rarely I write two articles on a single subject in one day (and certainly not this late at night). However, I’m genuinely enthused about this latest initiative by the Family Justice Council and British Psychological Society. It’s a matter I’ve been talking and writing about for the past two years.

Last year, I worked with Families Need Fathers making proposals for improvements in family law related to contact disputes and cases involving child alienation. These were presented to the President of the Family Court at a meeting last September. My belief (then and now) was that there should be greater collaboration between the courts and organisations such as the British Psychological Society to develop and share best practice to improve outcomes. It’s a belief which is clearly shared and worked upon by others and I thank them.

In 2014, Practice Direction 25B, ‘The Duties of an Expert’ was a welcome step forward, but there needed to be more done to ensure practice directions are followed and due diligence done when practice directions are at times ignored in court proceedings. That, I believe, is a matter for Family Justice Councils to pursue.

Best practice sharing, feedback mechanisms and agreed standards are essential tools in improving outcomes and introducing consistency into court proceedings. This becomes even more important amongst the chaos caused by court closures, cutbacks and fewer parties having representation.

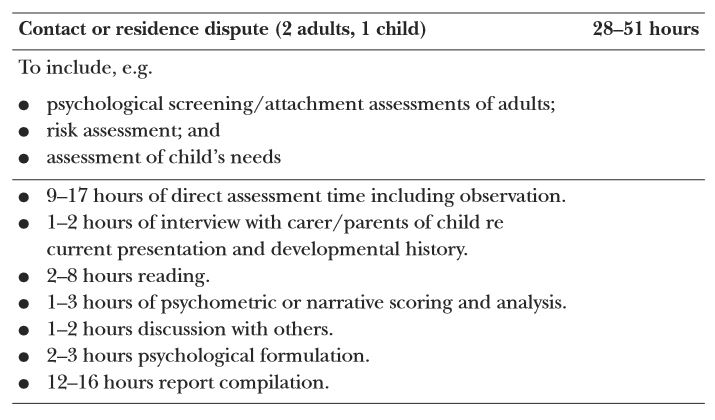

Expert reports are variable in quality and the joy of this new initiative and the intentions behind it are to not only set appropriate standards for psychological assessments, but to introduce feedback mechanisms to improve standards in expert reporting. The guidance goes further in giving examples of what psychological assessments should include (see the image below… the example being for contact/residence disputes). Make sure you read it!

Poor quality assessments, and the appointment of practitioners lacking the requisite skills and/or experience causes delay (often months), the need for additional assessments (costing the parties thousands), and risks poor outcomes for families. Delay in itself makes it more difficult to resolve cases. Past research showed 20% of those involved in court work as experts lacked the necessary qualifications, and a further 20% lacked the necessary experience. I doubt enough people carry out due diligence when proposing or considering an expert.

Poor quality assessments, and the appointment of practitioners lacking the requisite skills and/or experience causes delay (often months), the need for additional assessments (costing the parties thousands), and risks poor outcomes for families. Delay in itself makes it more difficult to resolve cases. Past research showed 20% of those involved in court work as experts lacked the necessary qualifications, and a further 20% lacked the necessary experience. I doubt enough people carry out due diligence when proposing or considering an expert.

To assist with due diligence, we have updated our own guide on Psychological Assessments which can be found in the Crisis Menu of our online guides. We have included:

- A download version of the new Psychologists as Expert Witnesses in the Family Courts Guidance

- Links to registers for psychologist practitioners.

- Links to relevant registering bodies for child psychotherapy, systemic family therapy, and other therapist counsellors who may be considered for appropriate family court work as experts. Bear in mind Practice Direction 25B sets out that the term expert includes a reference to an expert team which can include ancillary workers (in addition to experts) who may be considered experts in their own field.

- Links to professional conduct hearings and findings for each of these organisations.

- A download version of Practice Direction 25B, which includes the standards to which all experts in family proceedings should adhere and all those involved with cases involving experts should be aware.