Of interest to those involved in cases involving international child abduction, the unlawful retention of children abroad, applications for leave to remove, and applications for temporary leave to remove, comes new data from the United States on state non-compliance in respect of the children’s return.

The 2015 report from the US Department of State Bureau for Consular affairs records outcomes involving US children abducted abroad, and difficulties involving other countries and their compliance with the International Child Abduction Prevention and Return Act (ICAPRA).

The 2015 report from the US Department of State Bureau for Consular affairs records outcomes involving US children abducted abroad, and difficulties involving other countries and their compliance with the International Child Abduction Prevention and Return Act (ICAPRA).

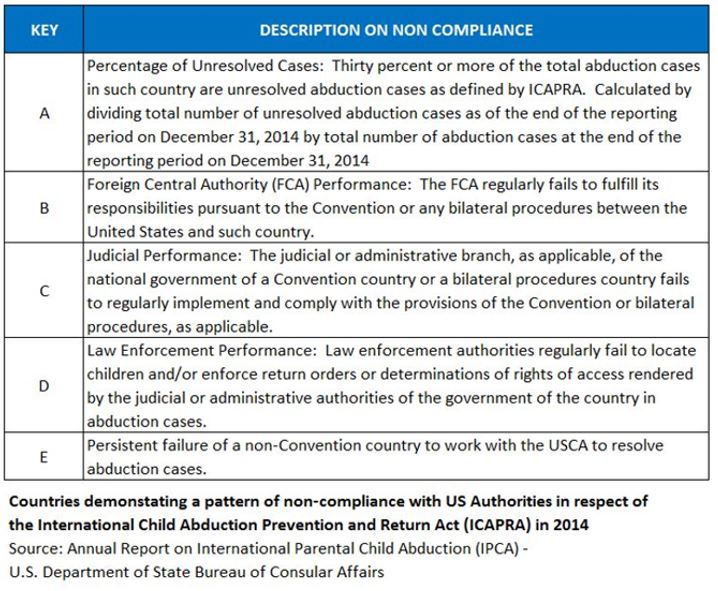

The ICAPRA was enacted by Congress in 2013 (and further revised in 2014), to help ensure compliance with the 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction by countries with which the United States enjoys reciprocal obligations and to establish procedures for the prompt return of children abducted to other countries.

The table below provides an explanation of the issues faced by the US Authorities:

Why are we highlighting the research (given it is a US report about US children)?

It’s recent. Secondly, those involved in seeking to defend against a leave to remove application (temporary or permanent) should consider and include in their arguments any difficulties which might be experienced in getting foreign courts/states to comply with UK orders, or have children returned to the UK if the courts grant temporary leave to remove (and there exists a risk of the parent taking the children abroad not returning them as promised or ordered by the UK court).

With regard to temporary leave to remove, guidance in Re K (Removal from Jurisdiction: Practice) [1999] 2 FLR 1084 (repeated in numerous judgments since) sets out that the court must consider:

- the magnitude of the risk of breach of the order if permission is given;

- the magnitude of the consequence of breach if it occurs; and

- the level of security that may be achieved by building in to the arrangements all of the available safeguards.

Affording expert evidence to assess how likely it is for a child to be returned following an unlawful retention abroad may pose a problem. Legal aid is pared to the bone, and the cost of expert reports and paying for an expert to attend court can be prohibitive. A state’s historic non-compliance with a country seeking the return of a child who is their citizen (or is habitually resident in the country seeking the return) presents information which may assist the court.

You should not assume that omission from the US report indicates there are no problems in respect of countries not listed. Some countries may have a better relation with the US than they do with the UK, there remains the issue of affording legal proceedings, and personally, I’m surprised to see some countries excluded from their data (given experience of cases where the return of children has taken years and huge expense). That said, if it is proposed your child or your client’s child is to be taken to one of the countries with which the US has had difficulties, and non-return by the parent seeking temporary removal is a risk, the report should ring warning bells and you should consider referring to it in evidence.

If you face an application for leave to remove, or temporary leave to remove, and wish further information on foreign countries and their compliance with international agreements and recognition of UK orders, we recommend contacting the charity Reunite. Similarly, Reunite provides support and advice to parents whose children have been abducted or unlawfully retained abroad or for those who believe their children are at risk of this.

You can read (and download) the 2015 report from the US Department of State Bureau for Consular Affairs via the following link:

Please also refer to the following guides: